Identify microservice boundaries

Architects and developers struggle to define the correct size for a microservice. Guidance often emphasizes avoiding extremes of too large or too small, but that advice can be vague in practice. But if you start from a carefully designed domain model, you can more easily define the correct size and scope of each microservice.

This article uses a drone delivery service as a running example. You can read more about the scenario and the corresponding reference implementation here.

From domain model to microservices

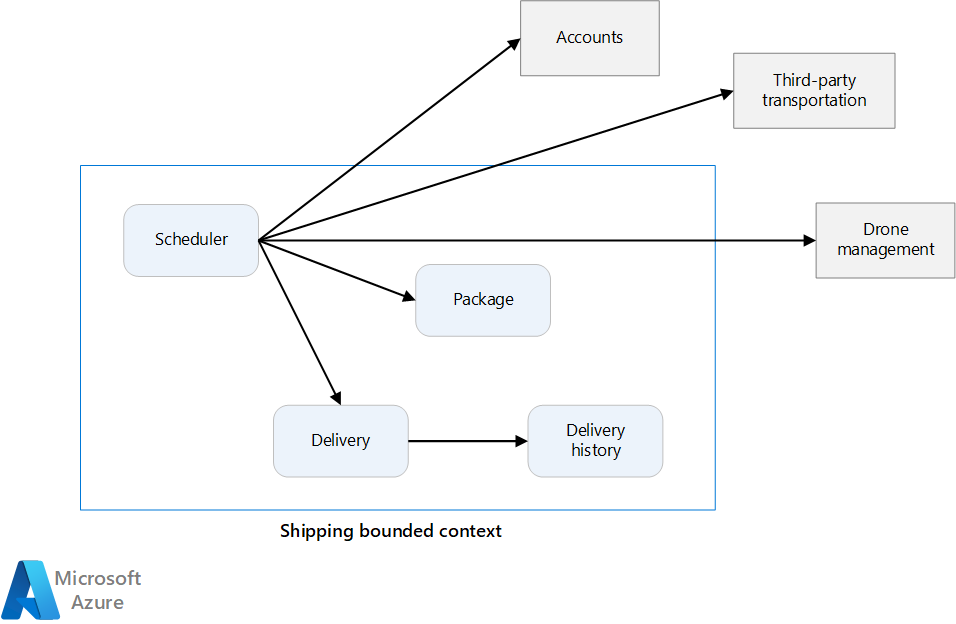

In the previous article, we defined a set of bounded contexts for a Drone Delivery application. Then we looked more closely at one of these bounded contexts, the Shipping bounded context, and identified a set of entities, aggregates, and domain services for that bounded context.

Now we're ready to go from domain model to application design. Here's an approach that you can use to derive microservices from the domain model.

Start with a bounded context. In general, the functionality in a microservice shouldn't span more than one bounded context. By definition, a bounded context marks the boundary of a specific domain model. If you find that a microservice mixes different domain models together, you might need to go back and refine your domain analysis.

Next, look at the aggregates in your domain model. Aggregates are often good candidates for microservices. A well-designed aggregate exhibits many of the characteristics of a well-designed microservice:

- An aggregate is derived from business requirements, rather than technical concerns such as data access or messaging.

- An aggregate should have high functional cohesion.

- An aggregate is a boundary of persistence.

- Aggregates should be loosely coupled.

Domain services are also good candidates for microservices. Domain services are stateless operations across multiple aggregates. A typical example is a workflow that includes several microservices. The Drone Delivery application shows an example.

Consider nonfunctional requirements. Look at factors such as team size, data types, technologies, scalability requirements, availability requirements, and security requirements. These factors might cause you to break a microservice into multiple smaller services. In other cases, they might cause you to merge several microservices into a single microservice.

After you identify the microservices in your application, validate your design against the following criteria:

Each service has a single responsibility.

There are no chatty calls between services. If splitting functionality into two services causes them to be overly chatty, it might be a symptom that these functions belong in the same service.

Each service is small enough that it can be built by a small team working independently.

There are no interdependencies that require two or more services to be deployed together. Each service should be deployable independently, without needing to redeploy others.

Services aren't tightly coupled and can evolve independently.

Service boundaries are designed to avoid problems with data consistency or integrity. In some cases, maintaining data consistency means grouping related functionality into a single microservice. However, strong consistency isn't always required. Distributed systems provide strategies for handling eventual consistency, and the benefits of decomposing services often outweigh the complexity of managing it.

Above all, it's important to be pragmatic, and remember that domain-driven design is an iterative process. When in doubt, start with more coarse-grained microservices. Splitting a microservice into two smaller services is easier than refactoring functionality across several existing microservices.

Example: Defining microservices for the Drone Delivery application

The development team previously identified the four aggregates, Delivery, Package, Drone, and Account, and two domain services, Scheduler and Supervisor.

Delivery and Package are obvious candidates for microservices. The Scheduler and Supervisor coordinate the activities performed by other microservices, so it makes sense to implement these domain services as microservices.

Drone and Account are interesting because they belong to other bounded contexts. One option is for the Scheduler to call the Drone and Account bounded contexts directly. Another option is to create Drone and Account microservices inside the Shipping bounded context. These microservices would mediate between the bounded contexts, by exposing APIs or data schemas that are more suited to the Shipping context.

The details of the Drone and Account bounded contexts are beyond the scope of this guidance, so we created mock services for them in our reference implementation. But here are some factors to consider in this situation:

What is the network overhead of calling directly into the other bounded context?

Is the data schema for the other bounded context suitable for this context, or is it better to have a schema tailored to this bounded context?

Is the other bounded context a legacy system? If so, you might create a service that acts as an anti-corruption layer to translate between the legacy system and the modern application.

What is the team structure? Is it easy to communicate with the team responsible for the other bounded context? If not, creating a service that mediates between the two contexts can help to mitigate the cost of cross-team communication.

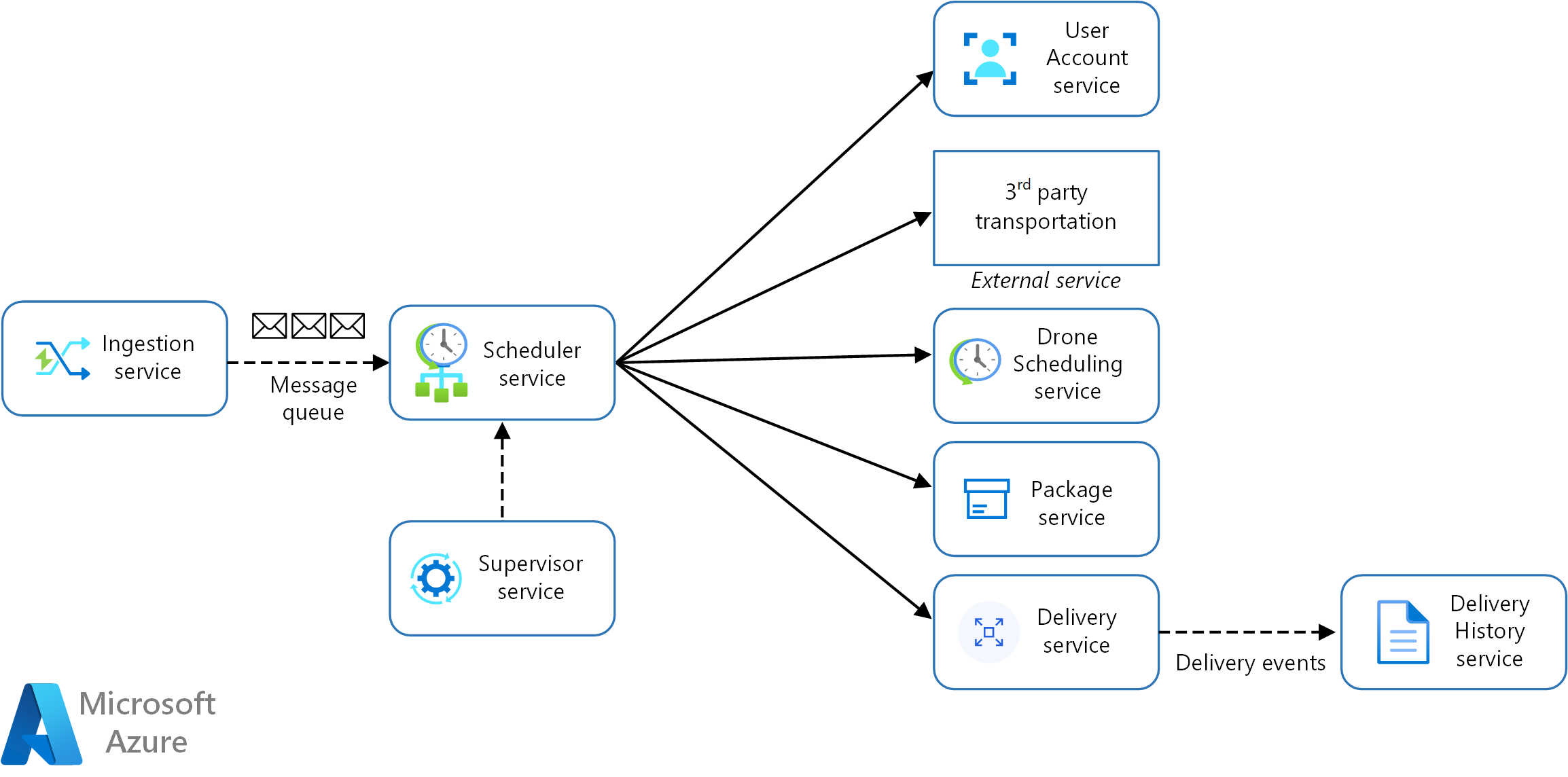

So far, the team hasn't considered any nonfunctional requirements. After evaluating the application's throughput needs, the development team creates a separate Ingestion microservice to handle client requests. This microservice implements load leveling by placing incoming requests into a buffer for processing. The Scheduler then reads requests from the buffer and implements the workflow.

Nonfunctional requirements also lead the team to create one more service. The existing services focus on scheduling and delivering packages in real time. However, the system must also store delivery history in long-term storage for data analysis. Initially, the team considered making this task part of the Delivery service. But the data storage requirements for historical analysis differ from the requirements for in-flight operations. For more information, see Data considerations. As a result, the team created a separate Delivery History service. This service listens for DeliveryTracking events from the Delivery service and writes them to long-term storage.

The following diagram shows the design at this point:

Download a Visio file of this architecture.

Next steps

At this point, you should have a clear understanding of the purpose and functionality of each microservice in your design. Now you can architect the system.